“Sometimes, the hardest brake to press is the one on your own ambition.” – Futurist Jim Carroll

In the world of leadership and innovation, we are wired for speed.

We obsess over acceleration, growth, and breaking barriers. But I am learning, in a very personal way, that the true test of discipline isn't how fast you can go—it's whether you have the discipline to go slow when every cell in your body screams "faster."

Because this is what you need to do when you have 'minor fractures' of the transverse processes on your spine, as can be seen in my CT scan after my incident in November.

Which means I am currently living with a bit of a physiological paradox.

I'm a guy who, at my age, is in pretty decent physical shape and always VERY active - and now the most important thing I can do is to be intelligently inactive.

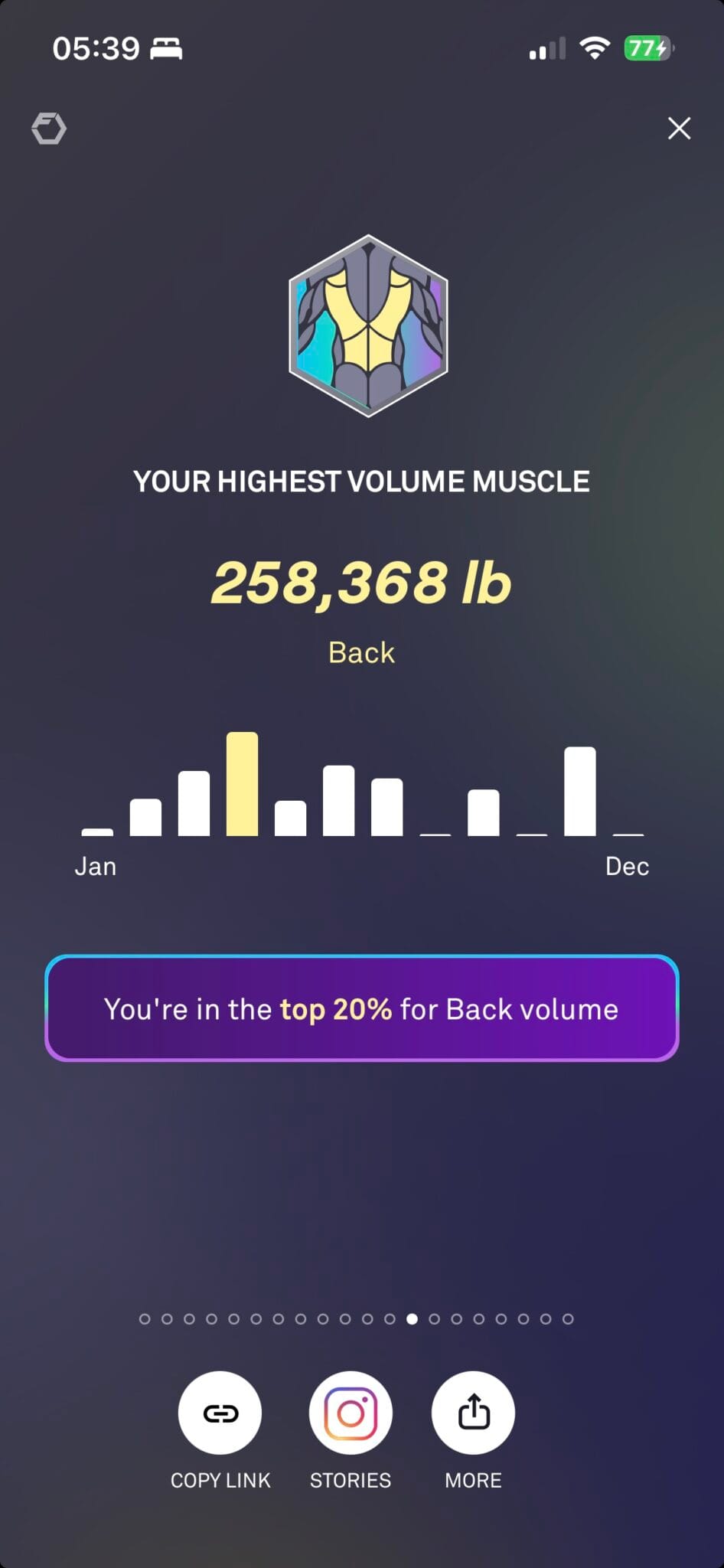

Let's start here. I use all the modern tools on my phone to track my fitness and health. And I must admit, I'm in pretty good shape. My resting heart rate averages about 52 beats per minute. That's athlete territory. My heart rate recovery is at the high end of the scale, dropping 38 beats in the first minute after exercise. That's really good! Not only that, but according to Strava, I was in the top 0.4% of all users for hours active last year.

And get this - I lifted a cumulative 884,000 pounds and built a back strong enough to land in the top 20% of all users. Google Gemini tells me that it was probably the fact that the back extensions I do were my #1 exercise that prevented my fall from being much worse, because I've built up so much muscle back there!

By every metric, my "engine" is primed, tuned, and ready to dominate.

But my "chassis" is currently broken.

Those three small fractures in my L1-L3 vertebrae don't care about my great VO2 Max. They don't care that I lifted a quarter-million pounds with my back muscles last year. They don't care that I spent a whopping 729 workouts last year, a combination of actual fitness routines, walking, and skiing.

They are fragile, healing, and demanding silence.

That means the most important thing I can do at this very moment is not to do much at all.

And for a guy who walks 7k to 15km a day, goes to the gym at least 5 times and week, skis for hours on a day during the winter - this is pretty overwhelming to try to do!

And this is where the leadership lesson hits home.

It is incredibly easy to be disciplined when you feel sick. When you have the flu, "resting" isn't a choice; it's a surrender. But it is agonizingly hard to be disciplined when you feel fit.

I certainly feel fit - '[m out mall walking (excitement LOL!), later on the treadmill. But I can't get back into the gym; skiing is done for the season; I've got to take it slow and easy.

That's the conundrum. Right now, I have the energy to ski 30,000 vertical feet. I have the stamina to walk 10 miles in the forest like I normally do. My "engine" - my fitness regimen - is idling at the red line, begging me to push the pedal and GO.

But if I listen to the engine, I destroy the chassis. That's my back. Those 3 small vertebrae are healing. They're still pretty fragile - I'm told I've got another 3 to 5 weeks to go before they have fully fused and are back to 'normal.'

Which means, in the meantime, "don't do anything stupid!"

Don't press GO. Don't fast forward!

And I must admit, being unable to press "GO" is pretty overwhelming!

And so with everything I do, I try to find the learnings - I try to see the leadership lessons in every situation.

Here's where this is leaving me. I see companies with massive resources (The Engine) trying to accelerate through a broken culture or a fragile supply chain (The Chassis). They think that because they can go fast, they should. And inevitably, they crash.

The hardest thing I am doing right now isn't the rehab exercises; it's the restraint. I am learning that restraint and showing down is not very easy. It is not a passive act. It is not "doing nothing." It is an active, aggressive protection of what I've got in terms of fitness and ability. If I go too fast, I ruin it!

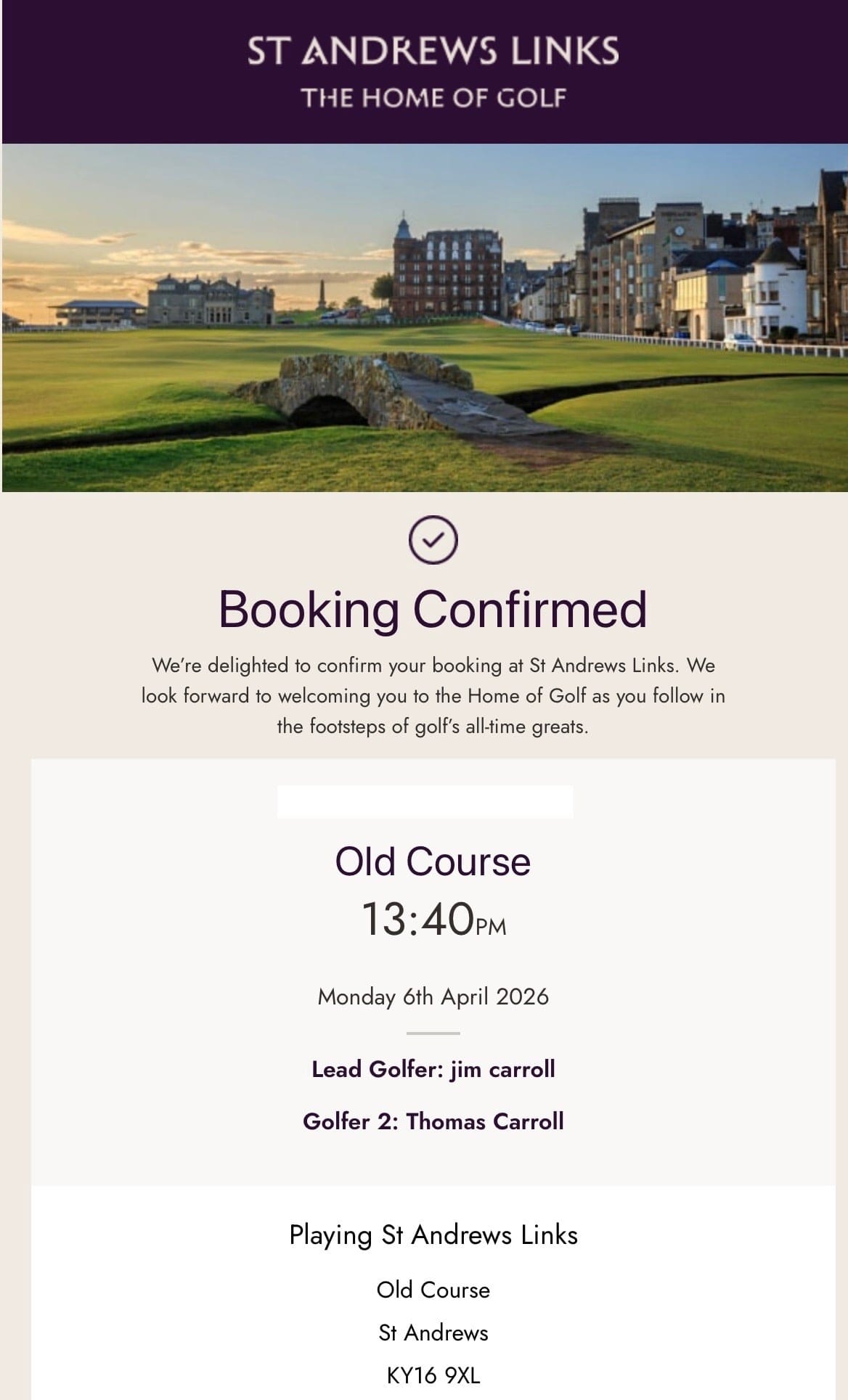

I am forcing myself to be in the slow lane, not because I can't go faster, but because I am smart enough to know that I need to go slow. My goal is my tee time at St. Andrews in April; my method to get there is to slow things down for now.

So today, if you feel like you are being held back, ask yourself: Are you being stopped?

Or are you being smart?

Sometimes, the most powerful move a leader can make is to simply take their foot off the gas.

Onwards!

(Slowly).

Futurist Jim Carroll is carefully learning that, in some situations, the future belongs to those who are slow.