To be a futurist is to be one who is often accused of getting the significance of various trends wrong. That's OK - we have to deal with the skeptics - it comes with the territory!

I've had some interesting reactions to a few of my trends pieces as of late. A few folks have dismissed my Vertical Farming post, part of my BIG Future series, suggesting that it will never amount to much, most of all because it won't 'scale' to meet the needs of millions of people. Last week, in an event with a number of CEOs, one fellow seemed to be rather dismissive of a move to electric vehicles, pointing out the recent challenge in California. Just days after a law was passed requiring that by 2035 that all new vehicles be electric vehicles, electrical utilities were asking people to NOT charge their cars because of excessive demand on the grid as the result of all the storms this winter.

In both cases, the basis for their skepticism is well founded and warranted - but misses the point that often, 'the future happens slowly, and then, all at once.' I think that will be the case with electric vehicles. In addition, I've long gone to the issue of the 'timing of the trend' to point out how the future might unfold. We can't expect that when a trend appears it suddenly matures: the most difficult thing about the future is not necessarily the trend but the timing. That's why I've got at scale' as part of the title of the vertical farming trend. The idea has existed for a time, but I believe the numbers are so compelling that at some point, it will only make sense that it will scale.

In addition, many trends 'co-exist': any trend does not necessarily replace something else. Some of the comments have indicated that some folks seem to believe that I am suggesting that vertical farming might replace most existing farming, but that's not the case. It's a trend that will co-exist with traditional agriculture forever - but the point is, we are at an inflection point with the idea and the technology behind it.

What's the basis for skepticism? It's certainly been the case that when we talk about the future and a trend, it has long been the reality of those behind the trend to 'over-promise but underdeliver; skepticism is warranted of any trend, considering history. particularly more so today in the era of 'TechnoSkepticism.' Many people feel burned by the future as the result of past-failed predictions: as the saying often goes, "I was promised flying cars, but instead, I got (something else.)'

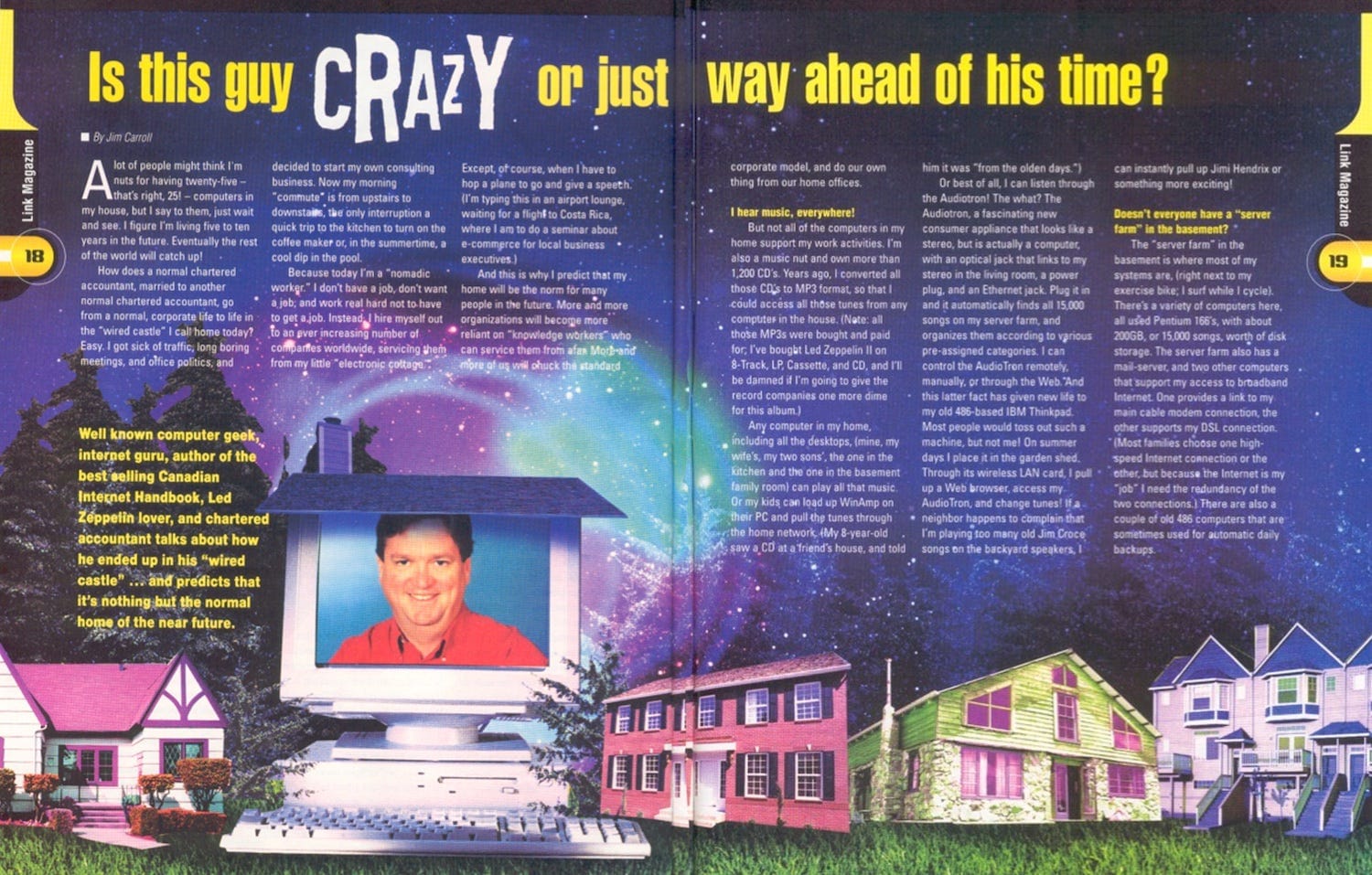

The danger with all this is that too much skepticism can cause you to lose sight of the eventual mainstreaming of any particular trend. Take the idea of the smart home and home automation; back in 1999 or so, the article 'Is This Guy Crazy or just way ahead of his time' ran in a magazine, taking a look at my 'smart home' setup. (I was much in the news back then; as the author of 34 books about the Internet, I did over 3,000 interviews on radio, TV, and print. (I kept track).)

If you want to read the article, the full PDF is here.

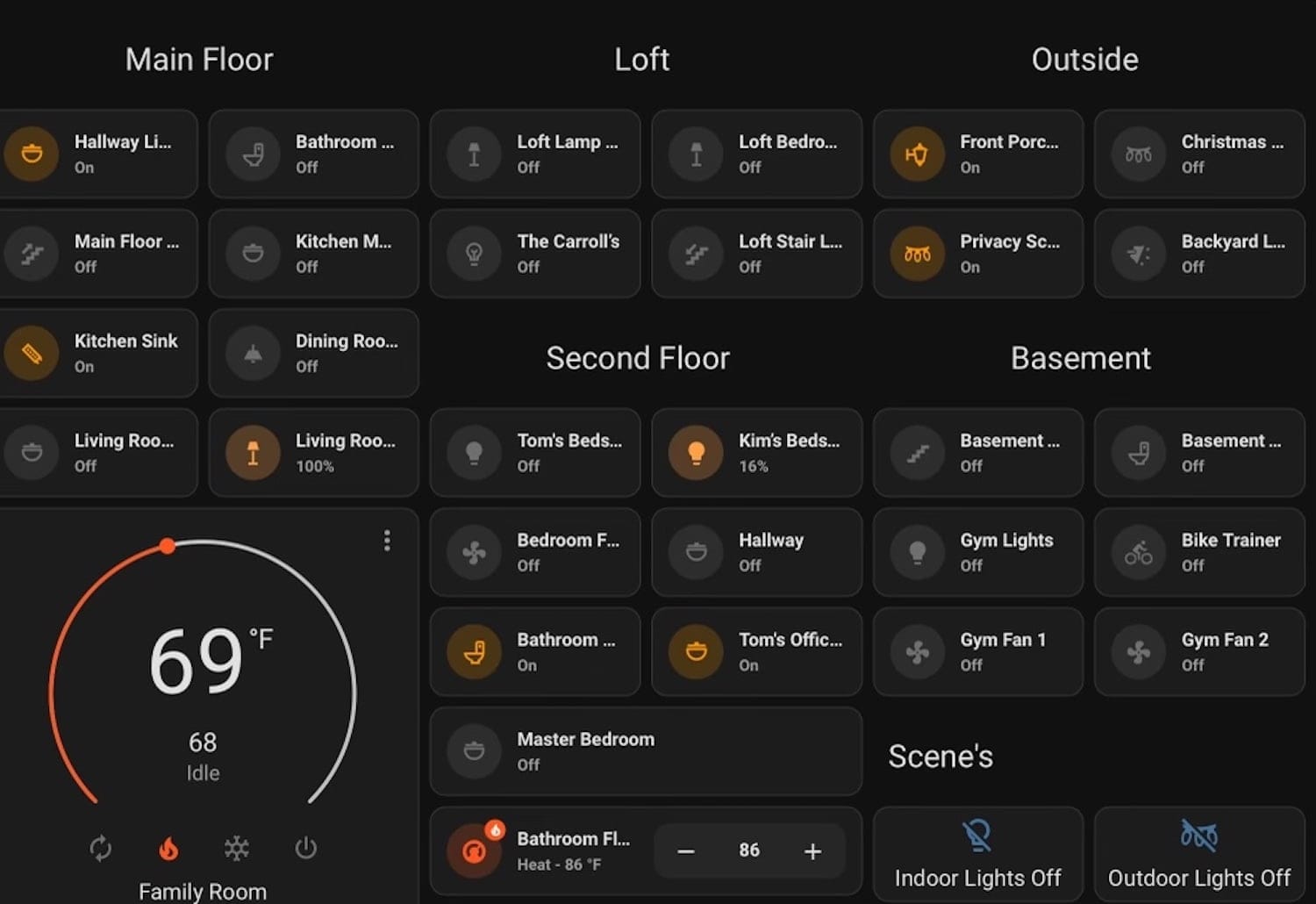

If you read the article, it all seems rather pedestrian now - in-home music via various devices, working at home, and wireless Ethernet. And yet, at the time, the article title deemed that I might be 'crazy' for doing such things. Yesterday crazy is now mainstream. Today? One of my sons has a crazy-smart 'smart home' - here's the screen for the iPad-based controller he has in place, by which he can control lights, switches, fans, and even the heated floor in a bathroom.

How about e-commerce and online shopping? Back in 1998 or so, my co-author and I released our book Selling Online: How to Become a Successful E-Commerce Merchant. Long since out of the print, the book sold in the US and Canada; a German edition was published, as was one for Russia. VISA liked the book so much that they did a bulk purchase of 50,000 copies, distributing it to various merchants at the time.

It was a fun project, but wow - did we ever run into skeptics?

We were admonished in the media for daring to suggest that vast numbers of people might actually buy things online; that most efforts were doomed to fail; that it was a fool's venture. This wasn't helped by the dot.com collapse of 2000, in which much of the blame can be laid at the feet of overhyped e-commerce: we had far too many companies busy establishing lofty goals with huge promises as to the extent of sales.

When those were proven wrong, stock markets lost faith. Oops.

But this had more to do with the timing of the trend rather than the trend itself - and as we all know, the acceleration of e-commerce and its adaptation rocketed as a result of Covid. Retailers who were busy getting involved with the trend before Covid had a far more successful transition to our world of lockdown than those who did not.

Online knowledge sharing and collaboration? In 1986, I suggested a project I called "Linkage" within the global professional services firm for whom I worked. I wrote the story of what happened in my book, Surviving the Information Age:

The intent was to unite professionals in various disciplines throughout the company through an electronic mail network so that they could share their own specialized knowledge. Many others had already begun their own informal networks; computer specialists across the country, for example, had been trading tips and ideas online for years. We found that tax professionals across the country were already plugging into each other, electronically exchanging their thoughts and reactions to the latest federal budget or new tax regulation.

My belief was that the “linkage” concept would provide the impetus for massive information sharing throughout the company, with the result that the business could better respond to clients, deal with competitive pressures and survive in an increasingly complicated world. I still passionately believe in the “linkage” concept today and see many thousands of organizations worldwide implement such projects.

But even back then the concept of “linkage” was not well understood by many in management. I was involved in many international projects and could see the benefit of global information sharing. But when my boss and I flew to New York to make a pitch to senior management, asking them to sponsor the project, which would encourage such information sharing on a global scale, our pitch was met with blank stares. They simply could not comprehend the concept that would capture the imagination of much of the rest of the corporate world through the next decade, even though they understood the competition was already moving rapidly to put in place such technologies.

Returning home from New York, dejected and flabbergasted, the trip turned out to be a first step in my decision years later to walk away from my 12-year career with the company. I simply could not live with what I believed to be blind stupidity.

Today, of course, corporate knowledge — the combined experience, wisdom, and awareness held by employees — has come to be recognized as an increasingly important resource and asset. Every leading-edge company, including, finally, my previous employer, has put in place sophisticated knowledge-sharing tools.

I seemed to christen my project with a name eerily similar to LinkedIn, which became a global collaborative knowledge network. Companies? Today, they continue to invest heavily in 'internal knowledge networking.'

The key point to all of this?

You can dismiss a trend - you can't deny it though.

You should never let your skepticism get in the way of the potential reality of a trend.

Futurist Jim Carroll is pretty proud of his 40-year track record in predicting the emergence and significance of various trends.